Marie Comuzzo, PhD Candidate, Brandeis University, Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Innovation Fellow 2025-2026, & Visiting Scholar, Kinney Center

Figure 1: "Psalterium Georgii, Fluvius Eridanus, Cetus, Officina Sculptoris, Fornax Chemica, and Machina Electrica," plate 28 in Urania's Mirror, a set of celestial cards accompanied by A familiar treatise on astronomy by Jehoshaphat Aspin, London.

Today, we know exactly what a whale is and what it isn’t. However, in the early modern period, before taxonomy neatly categorized all beings into fixed categories, “kētos” and “cetus” were fluid words that didn’t just encompass many dangerous and enormous creatures living in the ocean, but also, arguably, named the power of the ocean itself. This power was not confined to the deep either, it was mirrored above into the night, where among the stars, the constellation Cetus—a hybrid sea monster, part fish, part terrestrial being—guided mariners through the southern hemisphere (see Figure 1).

In Ancient Greek, kētos, “sea monster,” could mean a whale, a giant fish, or any enormous marine creature. Romans translated kētos into cetus, a Latin term that maintains a similar ambiguity. When the Old Testament and Quran’s story of “Jonah and the great fish,” later called “Jonah and the whale,” was translated from Hebrew, the being doing the swallowing, דָּג גָּדוֹל (dag gadol), literally “great fish,” was translated as “cetus grandis,” great cetus. The question of who, exactly, swallowed Jonah is a contested one in biblical exegesis, with answers including everything from a fish-god like creature, to a toothed whale, or even a shark, who is supposedly able to swallow a human in their entirety (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Figure 2 : Whale, men in a boat on its back. England c. 1236. The British Library.

Figure 3: “Jonah Bible Illustration.” Bible, Hainaut ca. 1280. Rouen, Bibliothèque municipale. ms. 185, fol. 130r.

Figure 4: Jonah Mosaic. Early 4th century CE. Mosaic. Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, Aquileia, Italy.

The historical accounts of whales, the biblical tale of Jonah, Conrad Gesner’s Historiae Animalium (1551-1558), and Adam Lonicer’s Kreuterbuch (1551), show how porous the boundaries between whale and the ocean truly were. Indeed, whales were not simply creatures living in the ocean. They were seen as the creators of tremendous storms and were often framed as intentionally wrecking ships, causing massive disasters, and more generally voicing god’s disruptive rage. These early accounts highlight how much the understanding of the ocean was framed through stories of mariners who survived such storms.

From a scientific point of view based on today’s knowledge of whale’s behavior, mariners must have witnessed whales breaching out of the water in unusual quantities during storms—something whales need to do in order to breathe in high seas—and most likely, this behavior was read as evil and dangerous. Indeed, if whales would have slammed at full speed into a ship, they would have certainty taken down said ship. The vulnerability that humans felt during these stormy encounters with the ocean and the whales might have established further a cosmological association between the two based on danger and human’s insignificance when faced to such power.

Figure 5: Conrad Gesner, “Animalium Mar. Ordo XII,” Historiae Animalium, National Library of Medicine (1551), 176.

This conflation of meanings persisted for hundreds of years, as clearly shown in the Historiae Animalium and the Kreuterbuch. Both published in the 1550s, these compendiums provide illustrations and categorizations of cetus and whales. In Historiae Animalium, Conrad Gesner gathers whales alongside sea monsters and sirens. In these early illustrations whales are frequently depicted as enormous fish/serpent faces with dangerous fangs, who rise to destroy ships and devour humans (see Figure 5).

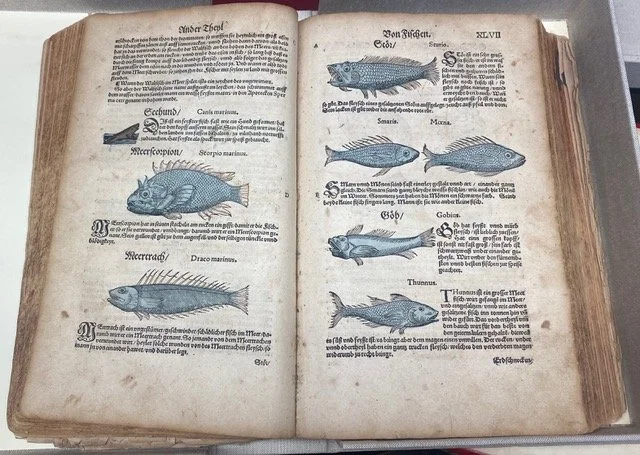

This is also true in Frankfurt physician Adam Lonicer’s Kreuterbuch, a vast herbal and natural history compendium published in 1551. This text contains images of human and nonhuman animals, as well as flora and more, and in it, “Walffisch/Cetus,” are among sea dogs, sturgeons, picarels, and tunas (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Adam Lonicer’s categorization of fish in his natural history taxonomy book. Held in the collection of the collection at the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies.

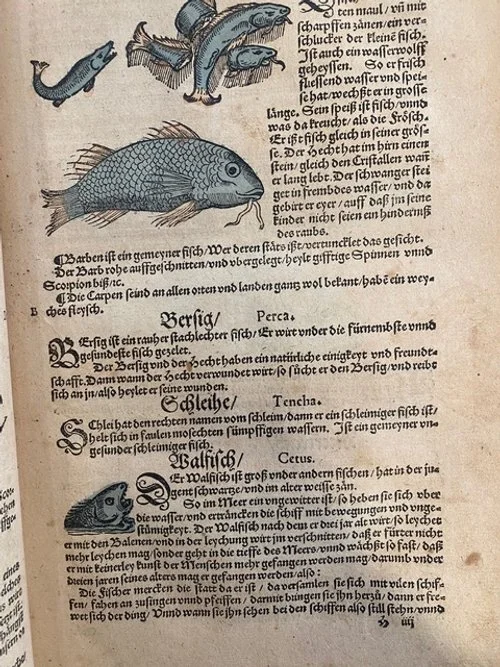

However, in Lonicer’s description the whale is not just massive in size, it also has a series of uncommon characteristics that are all jumbled up from what must have been a long series of accounts of all different sorts of marine creatures (see Figure 7). Thus, in this period the category of whale/cetus was highly unstable and included baleen and toothed whales, monsters with human or board heads, mermaids, and sea serpents. Perhaps these were not only so muddled because of the lack of specific information, but also because the aim was not so much biological accuracy as much as it was representing the devastating and overwhelming power of the ocean: a power that expressed itself through massive storms, animals, and human annihilation.

Figure 7: Adam Lonicer’s depiction and classification of the “Walfisch” (Cetus) under the category of fish in the Kreuterbuch. Held in the collection at the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies.

Lonicer’s description of Walfisch/Cetus states:

The whale is large among other fish and has black teeth when young and white when old. When there is a storm at sea, they rise above the waters and sink ships through their movements and violence.Once the whale reaches the age of three years, it mates with the Balenes. During the mating act, it is injured, so that it can no longer reproduce. It then goes into the depth of the sea and grows so greatly that it can no longer be caught by any human. Therefore, it can be caught only before it reaches three years of age, as follows:

The fishermen observe the place where it is, gather there with many ships, and begin to sing and whistle thereby luring it in, for it delights in such things. When they see it standing still by the ships, frightened by the sound of thunder, they secretly throw a large iron with sharp teeth onto its back and then flee. As soon as it is wounded, the whale flees to the bottom of the sea and rubs its back against ground, causing the iron to work its way in until it passes through the fatty layer to the living flesh. The salted seawater then follows the iron into the wound and kills it. When it thus lies dead, floating on the sea, the fishermen draw it to land with ropes, with great joy.

When the whale plays in the sea, it is a sign of a storm. When the whale releases its natural fluid during mating, it floats on the water; from this a white fatty substance is collected, called sperma ceti by apothecaries, and is of high value. [bold added]

This is the longest description of all “fish” present in the book, one that carefully lays out hunting techniques mixed with behavioral patterns and danger warnings. Whereas other fishes are mostly passive in these descriptions, the whale, according to Lonicer, is a powerful entity that controls storms, sinks ships, and must be tricked and lured through singing to be hunted. In this sense, the whale has most of the characteristics of the ocean itself, including force, unpredictability, danger, bounty, all of which require collaboration and high skill levels among humans to navigate its capture.

Whereas today “whale” means something very specific, in the sixteenth century “cetus” described something broader: a force of the ocean that could be expressed as fish, sea serpent, mermaid, whale, and more. As we can see in the Kreuterbuch and Historiae Animalium,“cetus” embodied a sense of awe, danger, and vulnerability—a force to be navigated and controlled, as much as it was to be feared and revered. This force was as present as above as below, where the shapeshifting sea monster in the sky directed sailors into the night, the same people who would sometimes face whales as the physical manifestation of ocean’s power. Thus, before modern taxonomy and more broadly before the scientific split of nature into fixed categories and species, “cetus” carried a plurality of meanings far beyond the modern word “whale.” This shift didn’t just reflect a heightened specificity; it also severed whales from their role as living embodiments of the ocean’s power. In stripping away their mystical force, we also stripped away a reminder of human vulnerability as well as a more just and respectful relationality towards our ocean kin.

References:

Adam Lonicer, Kreuterbuch (Franckfort am Meyn, 1564). Arthur F. Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies, Amherst, MA.