by Renaissance of the Earth Fellow, Hannah Gould

Hungry Earth

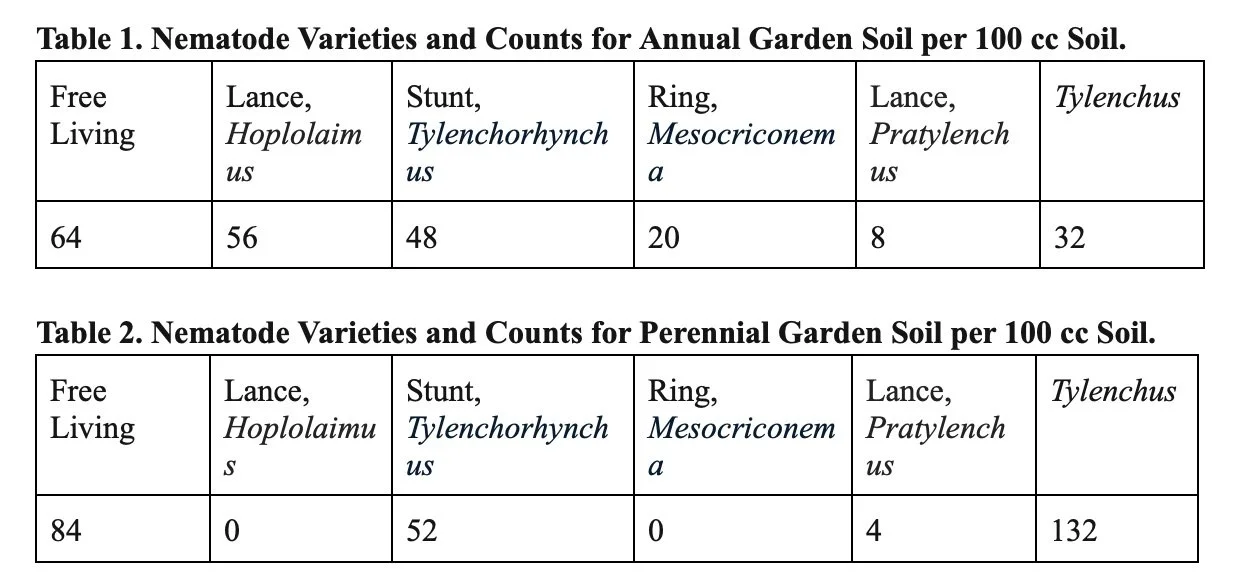

In my recent entries, I’ve shown a lively microscopic earth roaming beneath our feet. In that microscopic earth we are witness to a beautiful cycle of life and death into decomposition through the lives of wriggly nematodes helping to balance out the soil foil web. As organisms face climate instability and ecosystem degradation, it is crucial that we are considering not only what is above but also belowground. After all, our lives depend on these tiny creatures!

Thinking with the early modern past can help us shape this narrative. We may consider questions such as: How did early moderns judge soil health without access to modern technology? How did early moderns perceive creatures in the soil? Did early moderns face drought in the soil affecting their plants? What was the solution? For early modern agriculture, process was the answer.

In Digging the Past: How and Why to Imagine Seventeenth-Century Agriculture, Frances E. Dolan describes an early modern ideology behind soil “not as a given but a work in progress” (15) that “favors art over nature, process over place” (23). For today’s agriculturalists, quick fixes overpower the process that goes into maintaining healthy, balanced soils. As large-scale, industrial production overpowers our food system, we introduce more harm to our soils and organisms. This kind of production leads to increased chemical inputs on crops and harmful use of antibiotics in livestock (NRDC). As a result, we need to pivot to something more sustainable and be increasingly mindful of our waste streams. Professor Dolan has been thinking about soil as a process based on early modern teachings, amplifying authentic compost as the answer to our troubles. She claims compost as “rooted in the ground, absorbing the waste products of a particular place and enabling a given locale to remain productive over time” (23). Professor Dolan highlights a significant element of composting which resonates with our consideration of soil as living. Compost as a means to absorb waste and maintain soil as “productive” is crucial to viewing soil for what it actually is: a living being which needs tending, and not a virus that can be cured with a vaccine. While producers use chemical solutions to deter pests and disease, they are unknowingly killing the beneficial organisms which contribute to the health of our food systems.

John Worlidge’s 1681 Systema Agriculturae at RC Rare S509 .W6 1681

During the Renaissance of the European North, John Worlidge’s 1681 Systema Agriculturae at RC Rare S509 .W6 1681 wrote “labour seems to be the best soil” (84). For early moderns, chemical fertilizers and pesticides did not have a seat at the table. In Digging the Past, Professor Dolan illuminates labor as a “fundamental ingredient in compost” (23), emphasizing the importance of stewardship when working with the land. Composting as a laborious task lends us a deeper understanding and connection to fertility and abundance within soil. In her full study of seventeenth century agriculture and practice, Professor Dolan continues by connecting composting through the early modern period to a principle of “one puts back into the soil what has been taken from it” (25). Her scholarship allows us to see how early moderns perceived soil health and fertility through the interconnectedness between labor, compost, and soil.

Walter Blith’s 1653 The English Improver at RC Rare S509 .B6 1653

For producers in the Renaissance, food security entailed investing time and energy into the land and soil. In The English Improver (1653) at RC Rare S509 .B6 1653, Walter Blith articulates, “[...] in all which were there but a little patience, and addition of a little more cost and pains, there would not be one foot of ground more lost, but a double or triple advantage raised upon it in few years, and ever after” (115). Blith’s campaigns for the labor which goes into a fruitful harvest is reminiscent of Worlidge’s call to labor for the best soil. There is a clear consensus that your “fruit” is dependent on working with and for the soil.

Maintaining the authentic kitchen garden has led me to appreciate the art that goes into cultivating abundant plants. It is of no surprise to seasoned gardeners that the upkeep and vitality of one’s garden is directly proportionate to the amount of care that’s put into it.

My time in the kitchen garden has shown me the realities of tending to land, even on a smaller scale. At the Kinney Center, we’ve guided our garden management similar to Dolan’s descriptions of compost piling. Particularly, welding “together symbolic and functional, practical and ritual” with a philosophy “rooted in a concrete space and dynamic” (42). For early moderns, gardening and food production depended upon ecological cycling. As I explored in my previous entries regarding nematology, our food web expands beyond the aboveground inputs and outputs from human intervention. The micro and macro flora and fauna that encompass our soil structures are perpetually at play.

Although early moderns did not have access to modern technology to understand chemical ratios and concoct chemical fertilizers, they did have a hand in feeding the soil. In Walter Blith’s The English Improver, Blith claims that all good stewards cast “fearn, rushes, or thistles, or any coarse straw, or trash whatever” to the ground to make a “very good” soil (152). Interestingly, he likens the materials to “trash” suggesting that composting, more specifically soil health, benefits from collecting our waste. Blith continues by adding the leaves of trees (152) as a means to improve soil health. In identical terms, Worlidge’s Agriculturae writes, “let him cast his water, fodder, litter, dung, weeds, etc. and there let them lie and rot together” (85). The practice of letting leaves and other tree debris decompose remains a staple of the Kinney Center. Each Spring we welcome the foliage dropped from the wild woods that surround us. The commonly misinterpreted “trash” offers a great feast for the lively organisms that populate our garden. By feeding our microorganisms, we are contributing to the soil food web, and therefore feeding ourselves!

John Worlidge’s 1681 Systema Agriculturae at RC Rare S509 .W6 1681

Turning to Worlidge’s Agriculturae, he shares similar findings regarding waste as the food of soil. Notably, Worlidge offers a more expansive array of options to choose from when feeding a hungry soil. Worlidge claims that there are many kinds of materials that may be used to feed and “enrich” (64) soils. Worlidge states, “some whereof are taken from the earth, as chalk, marle, clay, etc. others from the waters, as sands, weeds, etc. others also are the lungs and excrements of living creatures, and others that are several sorts of vegetables themselves, and other casual things, as soot, rags, etc.” (64). Worlidge attests that all of these are “useful and beneficial” (64) to the land and soil. Worlidge’s list guides readers towards the reality of what earth provides for us to help our lands, naturally. From minerals to animals to plants, we are surrounded by offerings from the natural world to recycle our waste and put back into the soil what we have many times taken away from it.

Thinking with the knowledge of Worlidge and Blith, scholars can refer back to Dolan’s views on soil, more specifically composting-as-a-process. When we work with our land, we discover that the soil is unsatisfied. Dolan wonderfully articulates the labor and time that goes into fostering generous land in an effort to reinstate balance.

I’ve seen through my work in the Kinney Center kitchen garden and library that the resources are there, dying to be explored and read! Thinking with the early modern past can help to inform our current land stewardship practices. The teachings within rare books emphasize the importance of minding creatures above and below the surface, putting waste to use, and inspiring ecological balance and cycling.

Soils are the backbone of our production systems, constantly adapting to changing weather conditions and providing necessary sustenance for the entire planet, despite our constant abuse and often too-rapacious appetites for consumption. As we persevere through an era of environmental uncertainty and catastrophe, it is important that we remain tethered to our figurative and literal roots. As our earth calls out to us for help, isn’t it time we answer?

References:

Dolan, Frances E. Digging the Past : How and Why to Imagine Seventeenth-Century Agriculture. 1st edition., University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020

Blith, Walter. The English Improver Improved; or, The Svrvey of Hvsbandry Svrveyed. Printed for John Wright, at the Kings-head in the Old-Bayley, 1653

Industrial Agriculture 101, www.nrdc.org/stories/industrial-agriculture-101. Accessed 22 Apr. 2025.

Worlidge, John. Systema Agriculturae. Thomas Dring. 1681.

Hannah would like to extend her deepest gratitude to the following individuals for their time and effort in making her independent study come to life. Without your help, it would not have been possible.

Hannah in the garden, Fall 2024

Nicole Burton, Stockbridge School of Agriculture

Liz Fox, Arts and Academic Coordinator at the Kinney Center

Jeffrey Goodhind, Kinney Center Librarian

Melanie Morgan, RoE Fellow

Marjorie Rubright, Director, Kinney Center & Associate Professor of English

Rob Wick, Emeritus Professor of Plant Pathology & Nematology