Bo Kim, Renaissance of the Earth Fellow, Kinney Center & MFA Candidate, Studio Art, UMass

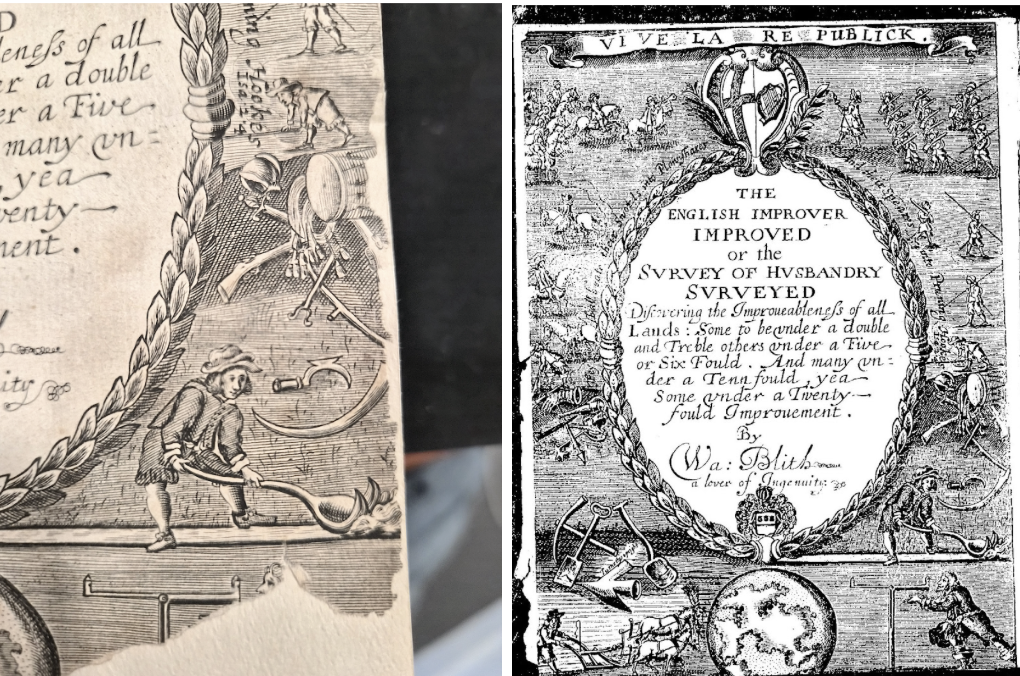

Figure 1. In this image, a well-dressed man presides over grafted plants and ordered gardens, surrounded by tools of pruning, measurement, and cultivation. Nature appears domesticated and ornamental. The scene aestheticizes domination, presenting cultivation as civilization and reinforcing the hierarchical relationship between man and land.

As a Renaissance of the Earth Fellow, I began my research by asking, “How can ancient tools speak to contemporary crises? What stories of repair, care, and survival do they still hold?” As I work with the Kinney Center’s archive, I notice that many early modern English books reveal a mindset of mastering and “fixing” the natural world rather than repairing or caring for it—a logic that parallels colonial domination (Figure 1 & 2). As a researcher, I trace how ecological control became foundational to imperial ideology–bodies of workers hunched in postures of labor exert themselves to control and order the land. As an artist, I reinterpret these images through re-drawing in an effort to unlearn the inherited colonial gaze (Figure 3).

Figure 2. This engraving depicts laborers systematically clearing and labeling the landscape, transforming the earth into a grid of stumps and data. Nature is rendered measurable and obedient—a surface to be improved, owned, and rationalized through human intervention. The image embodies a colonial gaze that equates the control of extraction with progress, marking the land itself as a conquered subject.

Again and again, I have found myself returning to the language of grafting. In the earth, grafting describes the joining of living tissues—a negotiation between rootstocks and scions that echoes processes of adaptation and survival. In the body, the same term appears in medical language: grafting skin, healing incisions, forming scars that record trauma and recovery. In art—especially drawing and printmaking—I find parallel gestures of cutting, layering, transferring, and re-binding materials to create new surfaces.

These shared terms—cut, join, heal, layer, root, and scar—describe both ecological and artistic regeneration. They allow me to think of drawing not as representation but as a kind of ecological surgery, a reparative act where image, matter, and memory reattach. The vocabulary of grafting thus becomes both an ethical and aesthetic framework.

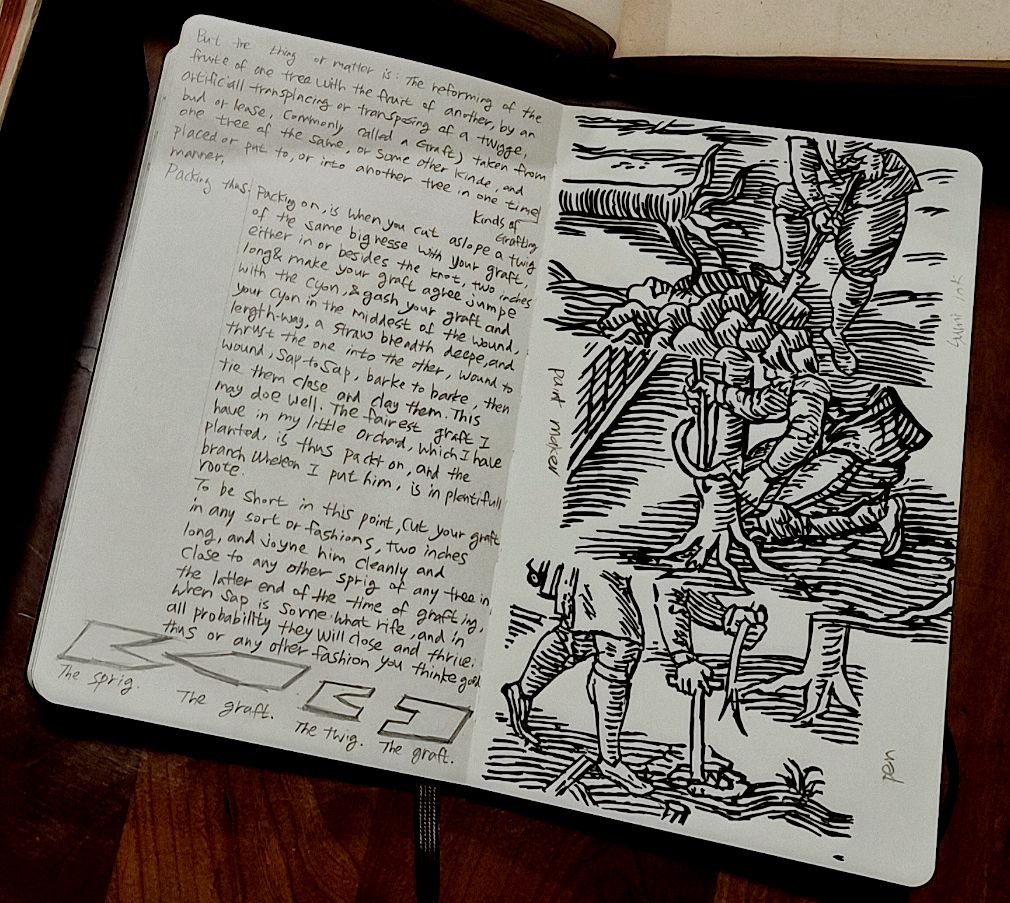

Figure 3. Bo Kim, Artist-Researcher Field Notebook.

Although I was initially interested in agrarian hand-tools deployed for working the land, I have come to view rare agricultural manuals themselves as Western “ancient tools”—repositories of ecological domination rather than care. By visually reworking them, I transform improvement into listening, extraction into exchange, and correction into coexistence.

My notebook (Figure 3) contains both handwritten reflections and a pen drawing derived from an early modern woodcut of grafting, a fitting together of pieces from different trees to produce healthier stock. On the left page, transcribed passages from a historical agricultural manual (Lawson, 1648) are interwoven with my own annotations, visually merging archival research with embodied interpretation. On the right page, a re-drawn ink study translates the original engraving into a tactile, gestural response—shifting a historical image of ecological control into a space for artistic inquiry and repair.

Here, as an artist-researcher, I participate in an embodied dialogue with the archive through my act of copying, which is not replication but instead re-interpretation. The sketchbook becomes both document and reflection, a living page where knowledge is grafted—connecting textual history, material observation, and artistic practice into one layered field of study.

During my research at the Kinney Center, I studied how rare books are repaired and preserved. Watching the meticulous reattachment of torn pages prompted me to reconsider repair as a form of grafting—a delicate joining of fragments where paper meets paper, memory meets touch, and preservation itself becomes an act of renewal (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Left: Rare book repair observed at the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies. Photograph by Bo Kim.

Right: The English Improver Improved (1649), digital scan from the University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.

How Do Different Cultures Imagine Repairing the Land and Where Do Their Stories Meet?

This archival research connects to my ongoing inquiry into agrarian tools such as the Korean Ho-mi (Figure 5), which carry communal memory and ethical relationships to land. Early modern English texts—The English Improver Improved (Blith, 1649), A Treatise of Cider (Beale, 1676), The Experimental Husbandman and Gardener (Agricola, 1726), and The Country House-Wife’s Garden (Lawson, 1648)—reflect an opposing worldview.

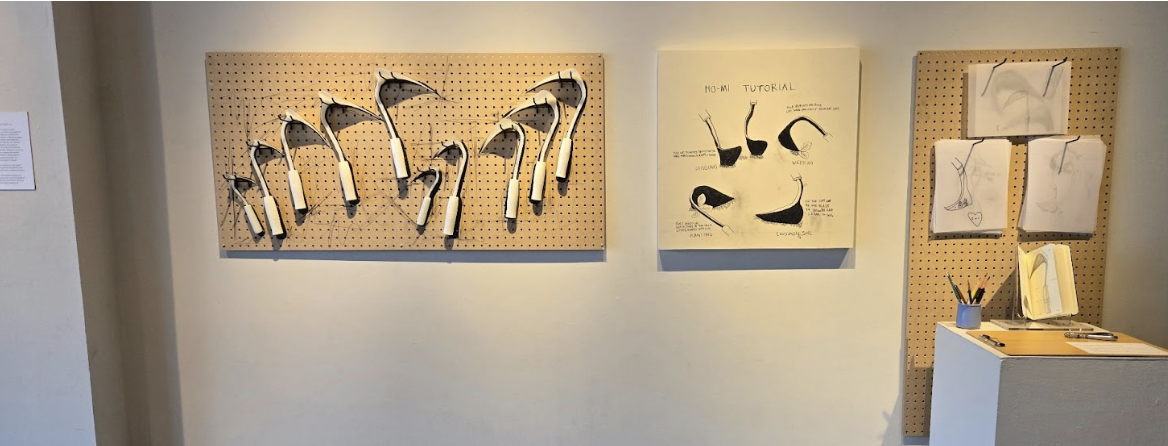

My ongoing research into agrarian tools—specifically the Korean Ho-mi, a hand-plow historically used in communal farming–aims to reinterpret the tool as a symbol of shared labor and cultural memory. Ho-mi Tool Station integrates sculpture, drawing, and participatory engagement to bridge craft, ecology, and pedagogy. On the left, a pegboard displays a series of Ho-mi tools, each 3D-printed and hand-finished to reflect variations in regional form and use. At the center, a “Ho-mi Tutorial” drawing serves as a visual guide, illustrating movements of the hand and wrist that echo both agricultural and artistic gestures. On the right, a participatory drawing station invites viewers to engage with the form through observation and mark-making—transforming a utilitarian tool into an instrument of contemplation.

Figure 5. Bo Kim, Ho-mi Tool Station Installation at A.P.E Gallery.

This research connects to my broader inquiry into agrarian material culture and embodied knowledge. I approach drawing not only as a foundational visual skill, but as a reflective practice that cultivates close observation, critical thinking, and material sensitivity—essential elements in fostering meaningful artistic inquiry and reconnecting contemporary art with ecological and communal heritage.

In this context, “grafting” functions as both metaphor and method in my artistic practice. In botany, it joins two living organisms so that they grow together while maintaining difference. To my mind, grafting symbolizes cross-cultural repair—binding dissonant worldviews such as Korean communal agrarianism and English colonialist husbandry to expose historical tensions while envisioning coexistence.

As metaphor, grafting represents decolonial translation and interdependence. As method, it informs my drawing and printmaking process, where roots, lines, and tool shapes intertwine across archival fragments, creating visual and conceptual hybrids that suggest healing rather than dominance.

What’s Next: How Can Rare Books Become Sites of Repair?

Building on the work of my fellowship, I am now experimenting with scoby, a microbial cellulose grown through fermentation, as an alternative to colonial parchment. Its skin-like texture evokes the rare books that codified imperial control. By drawing on this living membrane and grafting it to mulberry paper, I enact a union between microbial and human archives, East and West, life and decay.

The work asks:

How can we inscribe without conquering?

How can materials themselves become acts of care and repair?

Through this practice, grafting emerges not merely as a metaphor for survival but as an embodied method of ecological remembrance—a slow, reparative collaboration between human hands, microbial life, and ancestral memory.

Primary Early Modern Sources

Agricola, G. A. (1726). The experimental husbandman and gardener: Containing a new method of improving estates and gardens…

Beale, J. (1676). A treatise of cider.

Blith, W. (1649). The English improver improved: Or the survey of husbandry surveyed.

Lawson, W. (1648). A new orchard and garden… together with the country house-wife’s garden.

Images and Archival Materials

Bo Kim. Artist-Researcher Field Note. 2025. Photograph and drawings by the artist.

Bo Kim. Ho-mi Tool Station Installation. A.P.E. Gallery, Northampton, MA, 2024.

University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Scan of The English Improver Improved (1649). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A28382.0001.001/3